Generations under pressure - the impact on health

Young people today (Generation Rent) face the prospect of having to work longer, in more precarious employment, with more debt, more mental health issues, and reduced prospects of home ownership and a decent occupational pension compared with previous generations.

At the same time newspaper headlines have talked of ‘Deaths of Despair’ among the middle aged. The Institute for Fiscal Studies reported that deaths from suicide, drugs and alcohol are rising among middle aged Britons and now exceed deaths from heart disease in this age group.

Changes in employment, lifestyles and pensions have coincided with the rise of a debt culture fuelled by ‘financial services’ organisations. This means future generations face the prospect of years of retirement in poor physical, mental and financial health. They are likely to consume an ever-growing proportion of central and local government resources while finding themselves less able to contribute financially. That’s bad news for all concerned, from pensioners to the NHS, the government and the economy.

We’re already seeing that public health in the UK is worsening, on a generational basis. On current trends each generation will spend more years in poor health than their parents’ generation. Improvements in medical science were keeping people alive longer but this is increasingly in (expensive) poor health, with multiple medical conditions - and actuaries have identified that even the greater predicted longevity has now begun to stall. The well-publicised rise in childhood obesity (and a 40% increase in cases of avoidable type 2 diabetes in children in recent years) are powerful indicators of what lies ahead for the health of today’s younger generations, unless radical action is taken.

What have pensions got to do with health?

This might seem an unlikely connection but there’s a clear link between financial health and physical health. As the Office for National Statistics (ONS) has reported, men in better off areas live, on average, up to ten years longer than men in more deprived areas.

And it isn’t just how long people live but how long they live in good health. For instance, women in Tower Hamlets can expect to enjoy 14 fewer years of ‘healthy life’ compared with their more affluent counterparts in Richmond upon Thames.

We also know there’s a connection between our mental health and our physical health. So it isn’t, for example, just the reality of having to retire on a low income, in insecure rented accommodation in a deprived area that can influence your health – it is realising that this is what the future holds for you that can make a difference.

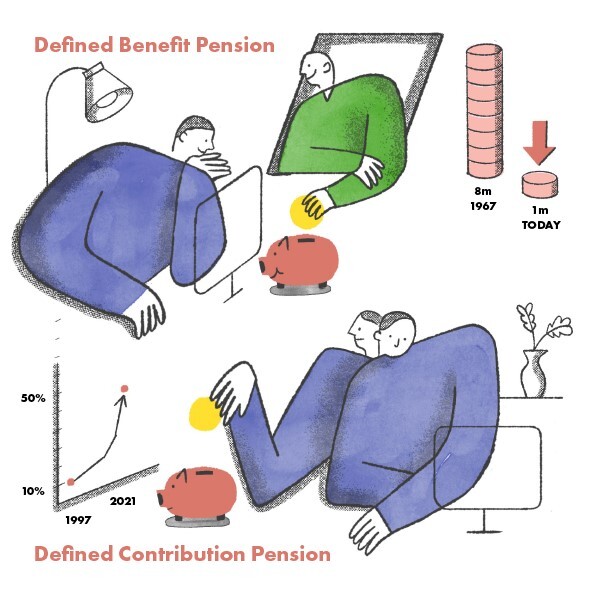

Occupational pensions should be a key element in helping achieve financial, physical and mental health in retirement. Unfortunately, occupational pensions have seen one of the biggest shifts in intergenerational fairness:

Art work by Chelsi Fu

- The number of private sector employees who can look forward to retirement on a final salary pension has fallen from some 8 million in 1967 to just 1 million today.

- In the public sector, final salary pensions are being replaced by career average pensions (further limited by pay freezes and pay caps and pension increases based on CPI rather than RPI).

- In addition, the rise of the gig economy, zero hours contracts and self-employment mean many people may have no occupational pension.

This is leaving more people reliant on a modest state pension, with a falling proportion of home owners meaning fewer people have property as an alternative asset to fall back on.

It is true that the State Pension Triple Lock, first introduced in 2010, has cumulatively improved state pension provision for pensioners. However, the state pension in the UK remains lower than in many comparable European countries and sometimes has to stretch further - for example where the UK has above average energy costs. There are also questions as to how financially sustainable it will be for the government to maintain the Triple Lock on a long term basis.

The decline in occupational pensions, exacerbated by a decade of minimal returns on savings, also fuelled the rapid growth of buy to let landlords. Rental income from property became increasingly seen as the only safe remaining savings/pension option. A 2016 study for the Council of Mortgage Lenders found that pension and investment purposes dominated the reasons for becoming a landlord. Buy to let landlords, in turn, fuelled an increase in house prices (with fewer houses available for home ownership, limited supply pushes up prices) while swelling the ranks of Generation Rent.

So what happened to occupational pensions and why?

Governments and employers have both contributed to the decline in occupational pensions:

- The Conservative government’s 1986 Financial Services Act introduced personal pensions and stopped employers requiring employees to join an occupational pension scheme. This led to the ‘mis-selling’ scandal of the 1990’s – with people persuaded to abandon their safer occupational pensions for riskier personal pensions.

- Some employers took a ‘holiday’ from making pension fund contributions when the Stock Market was booming (withholding £11.5 billion in pension contributions between 1995 and 2000, leaving their pension funds vulnerable when there was an economic downturn).

- In 1997 the Labour government, also seduced by an apparently never-ending rise in the Stock Market (which would crash just a few years later) took the decision to abolish tax relief on pension fund investment earnings – which has been calculated as now costing pension funds £10 billion a year.

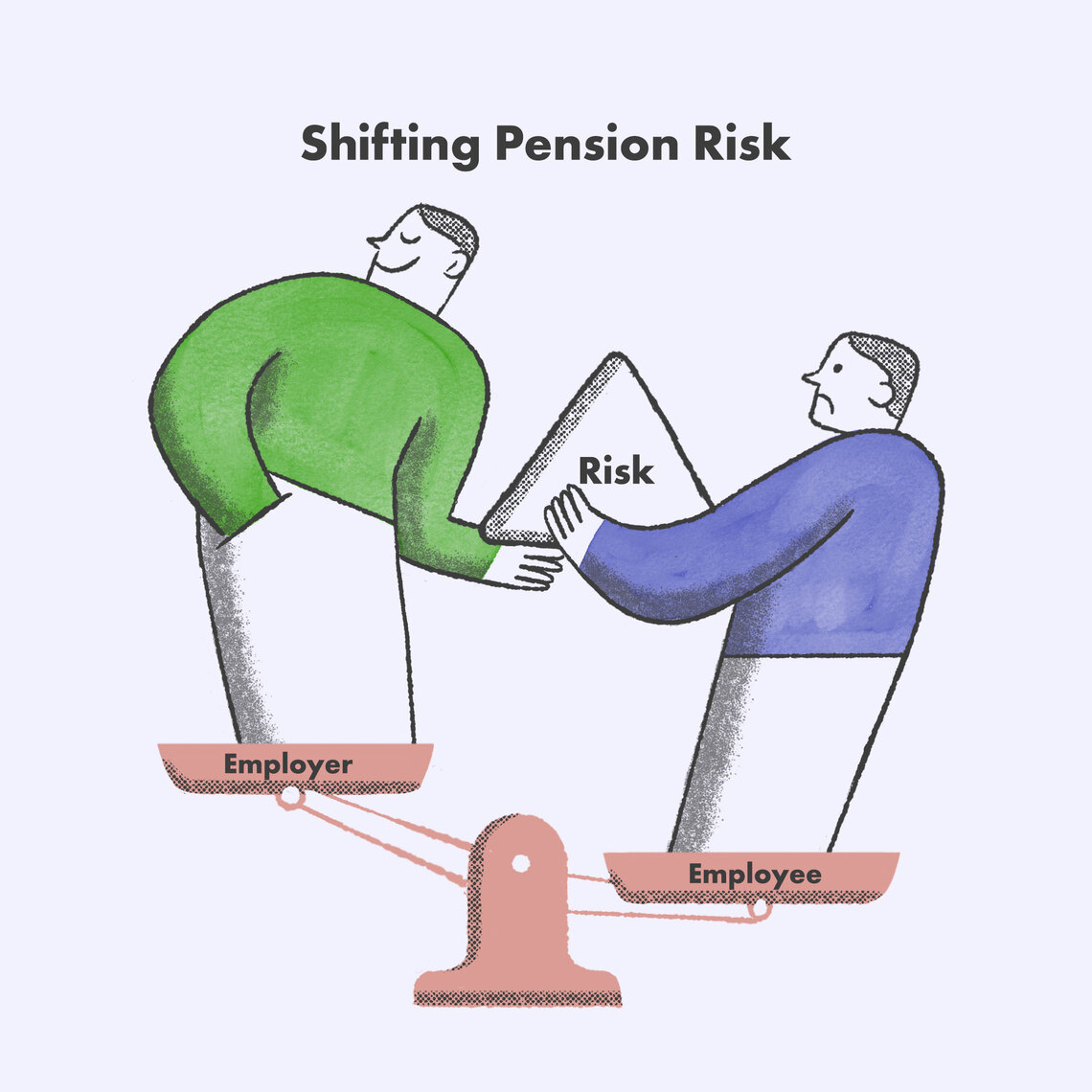

- Employers have increasingly shifted pension risk from themselves as an employer to their employees, by moving from defined benefit schemes (where employees know what pension they will receive, usually based on their salary) to defined contribution schemes (where the employer typically makes a smaller employer pension contribution and with no guarantee what the pension received will be, as this is dependent entirely on the pension fund’s performance).

- The Pensions Act 2004 required trustees to commission a “technical valuation” of their scheme at three-year intervals. As a former Governor of the Bank of England has commented, this technical valuation is sometimes based on over pessimistic historical assumptions. As an unintended consequence, government action intended to protect pensioners in the event of a defined benefit scheme closure has resulted in the continuing closure of defined benefit schemes, as pension funds struggle to meet their ‘technical valuation’ targets.

Art work by Chelsie Fu

Why am I focusing on occupational pensions?

Many different factors influence health in the UK. Some (like social inequality or the obesogenic environment) are significant but the result of many different factors, meaning there are probably no quick fixes. A wide range of action is needed to tackle them.

Occupational pensions are different. If most people could look forward to a reasonable occupational pension, based on their earnings, their prospects of a healthy retirement (not only financially but also mentally and physically) would be improved. This in turn would reduce pressure on the NHS and on social care, while providing a boost to the UK economy, through the enhanced spending power of pensioners.

It would also help address tension regarding the huge disparities in incomes between those at the top and bottom of many organisations, as seen in media comparisons of pay and working conditions for those working for companies like Amazon and Uber, compared with the incomes of their founders.

If occupational pensions provide a reasonable income in retirement then there would also be less need to rely on property as an investment rather than a home to live in, helping keep houses more affordable.

The main reason occupational pensions aren’t working as they should is specific action by governments (both Conservative and Labour) and specific action by employers – and these specific actions could be reversed. This means that changes here are potentially more achievable.

Recommendations

Government and employers have primarily caused the occupational pensions crisis. So it would seem only reasonable that they should take the lead in helping redress the balance. For example:

- The government could revitalise occupational pensions by reintroducing an element of tax relief on pension fund investment earnings, alongside its plans to encourage UK pension funds to invest in the country's economic growth.

- The government could review the technical valuation requirements set out in the 2004 Pensions Act, to ensure that pension schemes remain financially robust while avoiding the unintended consequence of viable defined benefit pension schemes being required to close.

- As and when economic circumstances permit, the government could consider how best to incentivize both employers and employees to contribute more fully to occupational pension schemes.

Michael Baber - updated February 2025

Continue the conversation with us on Twitter - @Health_ActionUK