The COVID-19 pandemic, combined with the impacts of recent conflicts, disasters and disease outbreaks, drove high inflation in a range of countries, causing the livelihoods and health of billions of people to deteriorate. The effect was to drive up the price of essential goods and services necessary for health, including housing, water, energy, food and transport. Inflation has now fallen in most developed countries but this simply means prices are rising less slowly, not that they have stopped rising, and the UK’s inflation remains the highest in the G7. This means high prices for essentials are continuing to impact UK households significantly. Making it increasingly difficult for many to afford basic necessities (1,2).

In addition, the UK National Health Service (NHS) is under severe pressure, which is important in terms of health inequalities. As of March 2025 7.4 million people remain on hospital waiting lists. Local services of the NHS report vacancies totalling over 112.000, with workforce gaps projected to reach 260.000-360.000 by 2036. The UK has fewer hospital beds, doctors, scanners, and nurses per capita than similar high income countries and although it’s efficient in areas like generic prescribing, long waits and lagging health outcomes remain pressing concerns (3,4,5). When considered together, the workforce gaps in the NHS, inadequacies in primary and community care practices, and the need to improve public health all pose a risk for health inequalities.

Housing costs

Housing is one of the most essential needs for living standards. It constitutes one of the largest expenditure areas of most families. Among the basic expenditure categories, housing in the UK is the most expensive compared to other advanced economies and is 44% more expensive than the OECD average. In fact, the UK has the largest gap between the cost of housing and the aggregate price level for household consumption out of all OECD members (6).

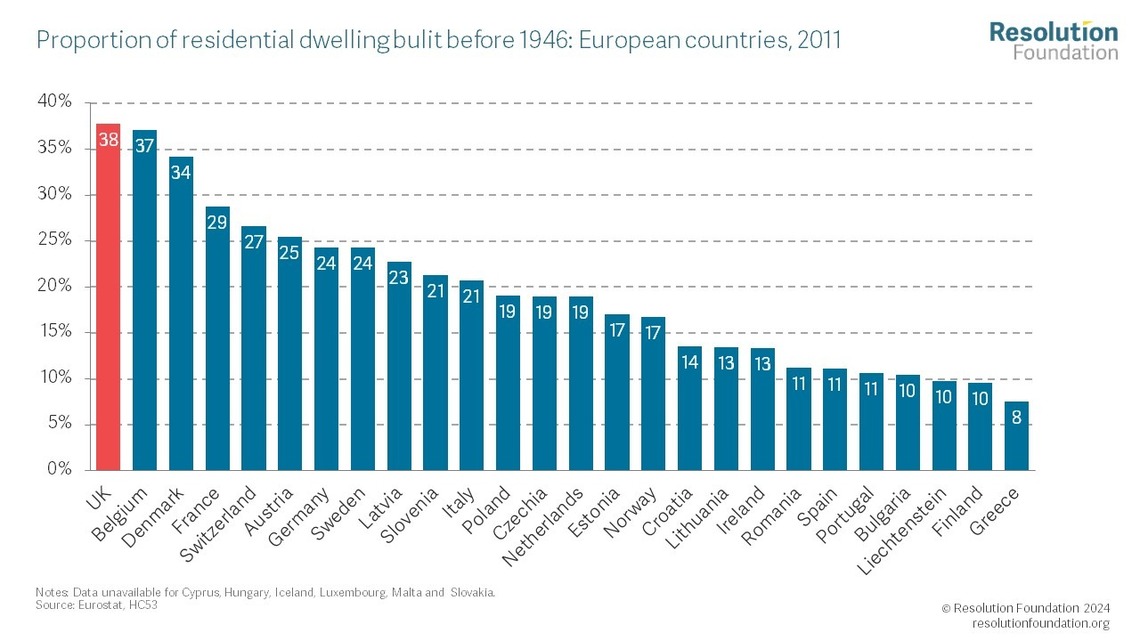

The UK’s housing stock is also the oldest in Europe at 38% (four in ten homes were built before 1946). This is more than double the EU countries’ average (18%) and higher than France (29%), Germany (24%), Italy (21%) and the Netherlands (19%) (7).

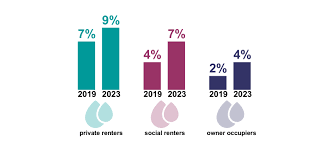

As a result of the age and poor quality of housing stock in the UK, energy bills are adversely affected due to poor insulation. Average homes are likely to be less energy efficient, less resilient to extreme weather conditions and generally in a poorer state of repair than newer homes. According to a report by the Grantham Institute, 28.6 million homes in the UK are among the least energy efficient in Europe, losing heat three times faster than on the continent, making people poorer and colder (8). The last English Housing Survey shows damp increased across all tenures since 2019, and was more prevalent in the private rented sector (9%), compared to the social rented sector (7%) and owner occupied sector (4%) (9). Sufficient epidemiological evidence is available from studies conducted in different countries and under different climatic conditions to show that the occupants of damp or mouldy buildings are at increased risk of respiratory symptoms, respiratory infections and exacerbation of asthma. Dampness and mould may be particularly prevalent in poorly maintained housing for low-income people. In the light of these results, energy-efficient housing design is worth considering. It can help reduce noncommunicable diseases associated with exposures to extreme heat and cold, indoor air pollution, as well as asthmas and allergies associated with chronic damp and mould (10,11).

Figure 2: Damp increase between 2019-2023

Source: The English Housing Survey, 2023

The shortage of good quality, affordable housing in the UK is a significant issue. The UK compares unfavourably with, for example, The Netherlands, whose large, well-managed social housing sector has proven to keep costs down and improve security, with social housing now accounting for 29% of the country’s housing stock.(12). However, an OECD 2025 report notes that housing affordability remains an issue in The Netherlands, as ‘Policies favouring owner-occupied and social rental housing over private rentals have created imbalances in tenure options and reduced housing market efficiency.’ This suggests that getting the balance right between owner-occupied, social housing and private rental isn’t easy. (13)

Past UK schemes like ‘Help to Buy’ raised prices without boosting supply. Even where there have been initiatives to create more affordable housing, these are often circumvented by developers, who use legal loopholes (in particular financial viability assessments) to avoid building the number of affordable houses they are supposed to. (14)

Energy Costs

When it comes to price, UK domestic gas prices in the second half of 2024 were below 16 EU countries. While gas prices have risen in recent years, these have been in line with other countries. The increase in gas prices in the three years to the second half of 2024 was 54% in the UK compared to 58% on average for the EU.

However, UK electricity prices were higher than in all but three EU states (Germany, Denmark and Ireland). Electricity prices in the UK have gradually become more expensive than in most other EU countries. In the early 2000s domestic electricity prices were the second lowest in the (then) EU 15 (15,16). UK electricity prices rose by 46% in the three years to the second half of 2024, substantially faster than 22% increase average for the EU and faster than in all but two EU states (17). Energy prices have fallen somewhat since this ‘energy crisis’ but remain well above earlier levels.

One consequence is a relatively high level of fuel poverty in the UK, with a government report indicating that in 2024 there were an estimated 11.0% of households (2.73 million) in fuel poverty in England (18) This exacerbates health inequalities, as cold, damp homes increase health risks – including strokes and heart attacks for older people; respiratory diseases including flu; and depression and anxiety. (19)

Unemployment Benefits

The UK has one of the lowest net replacement rates (NRR) for unemployment benefits among OECD countries. Net replacement rates in unemployment indicate the share of previous employment income retained after several months of receiving unemployment benefits. In the UK, the NRR stood at 17% of former in-work earnings, compared to an OECD average of 62%. After six months of unemployment, the UK ranked third lowest in the OECD, and after five months, it placed 30th out of 38 countries (20). As a result, unemployed individuals in the UK have less income available to cover rising household expenses compared to most other high income nations.

Not only are the unemployment benefits lower in the UK but also workers who move out of work in the UK face a risk of experiencing a large income loss that is greater than that in most OECD countries, including almost all western European economies. The cost to a household of job loss is 22 per cent in the UK, more than double the rates in Denmark, Finland and Germany (at 10%, 10%, and 8.6% respectively) (21). Insufficient income protection during unemployment does not just affect short-term living standards. It is also one of the factors that shape long term wealth distribution, deepening the gap between the secure and the vulnerable.

Alongside financial support when unemployed there is a need for more support to help people progress from unemployment to secure well-paid employment, with potential examples here from other European countries, such as Denmark’s strong job training programmes. (22)

Wealth Inequality

Wealth also significantly influences people’s lives, shaping outcomes from housing to health. In the UK, wealth is distributed far more unequally than income. Between 2011 and 2019, the total wealth gap between the top 10% and the bottom 10% increased by 48%, rising from £7.5 trillion to £11 trillion. Over the same period, the gap between the top 10% and the middle 10% grew by 49%, from £7.3 billion to £10.8 billion. In addition to widening over time, the UK’s wealth gap is large by international standards. Among OECD countries, only the United States has a bigger absolute gap between the richest 10% and the bottom 40% (23). As wealth becomes increasingly concentrated in fewer hands, those without it face greater insecurity and fewer opportunities, leaving many more vulnerable to being pulled into poverty.

While wealth taxes might help reduce wealth inequality in principle, in practice they have rarely worked, as rich people and organisations can move their wealth to lower tax countries. This is a real challenge. One possible option might be to encourage philanthropy, with the prospect of leaving a historical legacy, as with the Gates Foundation in the US.

Cumulative Effects

The UK’s cost of living squeeze, weak income protection, and wide wealth gaps are linked: high prices strain budgets, low benefits leave little buffer, and limited assets magnify economical shocks. When prices are high, benefits are small, and people have few savings, it becomes much harder for families to cope with sudden changes like losing a job.

What action is needed

Some recent steps may help - such as raising the minimum wage, improving home insulation, adjusting Universal Credit and the Government’s recent manifesto to build 1.5 million new homes in England by the end of the Parliament. However, there’s still more to do.

- Make affordable housing more widely available by reducing the planning loopholes developers use to avoid providing the number of affordable homes promised.

- Agree a cost-effective government programme to improve home insulation and energy upgrades for households experiencing or at imminent risk of fuel poverty.

- Ensure housing support rises in line with real rents, provided this doesn’t encourage landlords to hike rental charges.

- Raise unemployment payments to a fairer level and make them stronger when the economy is struggling, while giving better help to prepare for and find work.

- Learn from other countries: adopt policies like Denmark’s strong job training and placement services, or the Netherlands’ large, well managed social housing sector which are proven to keep costs down and improve security.

- Explore the potential to expand individual and corporate philanthropy as a potential means of redistributing wealth

These changes could bring down the cost of living, give people more security if they lose their work, and help them build a stronger financial safety net to turn short term solutions into long term stability for those who most need it in the UK.

Hatice Berna Karakoc

Resources:

- World report on social determinants of health equity. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2025.

- National Institute of Economic and Social Research, 2025, “UK Living Standards Review 2025”

- 3.https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-7281/(Accessed date: 14.08.2025)

- https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/nhs-long-term-workforce-plan-2/ (Accessed date: 14.08.2025)

- Siva Anandaciva (2023). How does the NHS compare to the health care systems of other countries? The King’s Fund, Available at: https://assets.kingsfund.org.uk/f/256914/x/7cdf5ad1de/how_nhs_compares_other_countries_abpi_2023.pdf (Accessed date: 14.08.2025)

- https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/publications/whose-price-is-it-anyway/#:~:text=These%20spending%20differences%20matter%20precisely,out%20of%20all%20OECD%20members. (Accessed date: 11.07.2025)

- https://www.hbf.co.uk/documents/12890/International_Audit_Digital_v1.pdf (Accessed date: 01.08.2025)

- https://www.innovationnewsnetwork.com/uk-has-some-of-the-least-energy-efficient-homes-in-europe/28434/ (Accessed date: 14.08.2025)

- https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/chapters-for-english-housing-survey-2023-to-2024-headline-findings-on-housing-quality-and-energy-efficiency/introduction-and-key-findings (Accessed date: 01.08.2025)

- WHO guidelines for indoor air quality: dampness and mould. Bonn: World Health Organization; 2009

- https://www.who.int/teams/environment-climate-change-and-health/healthy-urban-environments/housing/strategies (Accessed date: 14.08.2025)

- van Duerson H. The People’s Housing: Woningcorporaties and the Dutch Social Housing System. JCHS Harvard University. 2023. https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/research-areas/working-papers/peoples-housing-woningcorporaties-and-dutch-social-housing-system

- OECD Economic Surveys: Netherlands 2025 https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-economic-surveys-netherlands-2025_2dd1f4aa-en/full-report/towards-a-more-accessible-and-sustainable-housing-market_84a37526.html?utm

- Hill S. How private developers get out of building affordable housing. New Economics Foundation. 2022.

- https://neweconomics.org/2022/02/how-private-developers-get-out-of-building-affordable-housing

- https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-9714/ (Accessed date: 01.08.2025)

- https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20250506-2 (Accessed date: 05.08.2025) ttps://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-9491/CBP-9491.pdf

- Annual Fuel Poverty Statistics in England, 2025 (2024 date). Department for Energy Security & Net Zero, March 2025. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/67e51e2cbb6002588a90d5d5/annual-fuel-poverty-statistics-report-2025.pdf

- Whitehead M, Taylor-Robinson D, Barr B. Fuel poverty is intimately linked to poor health BMJ 2022 doi:10.1136/bmj.o606

- https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/43979/documents/217876/default/ (Accessed date: 02.08.2025)

- https://economy2030.resolutionfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/From-safety-net-to-springboard.pdf (Accessed date: 10.07.2025)

- https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2025/06/the-role-of-subnational-governments-in-adult-skills-systems-country-notes_258f2060/denmark_3ecde396/e4e72885-en.pdf (Accessed date: 07.08.2025)

- https://files.fairnessfoundation.com/inequality-knocks.pdf (Accessed date: 04.08.