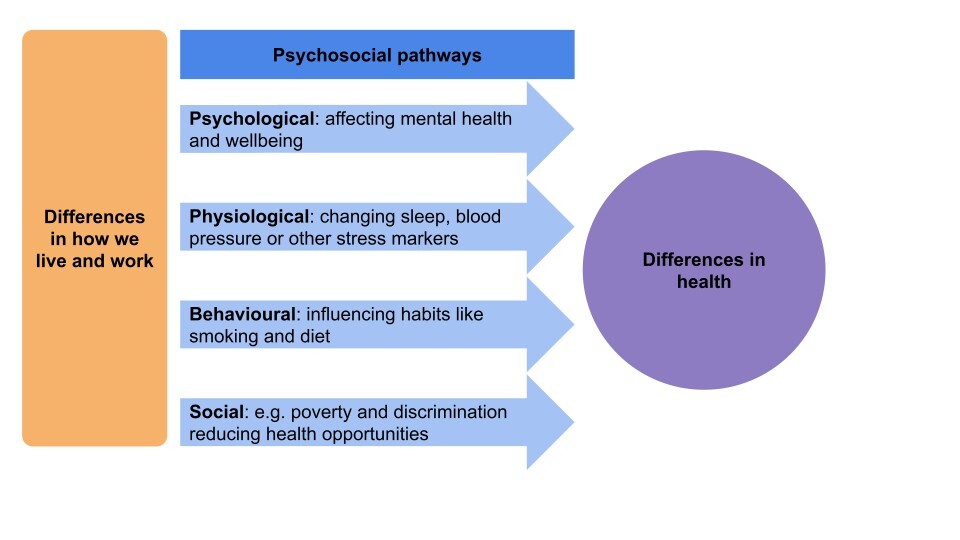

The way we live and work plays a powerful role in shaping our health and how long we live. “Health inequalities” are when certain people have worse health than others based on where they live, their circumstances (like income and housing) or characteristics (like gender). Psychosocial pathways are one explanation for how health inequalities actually happen. The pathways explain how our circumstances affect the way we think and feel, and how these thoughts and feelings then shape our health.1

We know that our health suffers when we have risk factors like feeling stressed, lonely, or feel like we don’t have control over our lives. People with these risk factors are more likely to have worse health, including a higher risk of cardiovascular disease and other conditions.1 Psychosocial factors can also be “protective”, for example if people feel resilient or have good social cohesion (trust and shared values with others), then they tend to have better health.1

The impact of psychosocial factors on health occurs through four main routes:1

The impacts on health can be long-term and there can be negative feedback loops, for example loneliness early in life can have later impacts on social relationships. Another example is that stress and negative emotions can cause people to focus on short-term happiness over long-term goals and have lower feelings of control, which can both be bad for our overall health.1

Although we know that psychosocial pathways are important for health, they are often ignored in efforts to tackle health inequalities.

What are the root causes of psychosocial pathways?

We explore three of the key drivers of psychosocial pathways that lead to health inequalities below.

Socioeconomic status (SES)

Low SES means having limited access to financial resources, education, and stable or well-paying jobs. People with low SES often face stress because of challenging living and working conditions, including poor-quality housing and less stable employment.2,3

This stress acts as a trigger for psychosocial pathways that worsen health, increasing likelihood of mental health symptoms, stress responses in the body, and harmful behaviours like smoking. People with low SES are also less likely to have positive psychosocial factors like strong resilience or feelings of control, because ongoing stress can use up available resilience, limit ability to develop these factors and reinforce feelings of negativity and hopelessness.2,3

Importantly, both “absolute” and “subjective” low SES matter for health. “Absolute” status is measured in terms of actual income or measurable factors, and “subjective status” is measured in terms of how we perceive our status (i.e. how do we see ourselves versus other people).2-4

Stigma

Stigma can come from actual or perceived low SES, as well as having a minority status in terms of ethnicity, sexual orientation, or other social identities. Stigmatised individuals often have higher levels of stress because of stigmatisation, isolation, poor levels of protective factors and higher risk of unhealthy behaviours such as smoking. These factors can then negatively affect mental and physical health.5

Early lifecourse influences

Early life stress, including poverty, can have immediate and longer-term impacts on health through “stress sensitisation”. This is when brain structure and function are changed in response to stress, which then causes long-term mental health issues, like anxiety, as well as physical health problems.1,3,6

Adverse childhood experiences include neglect, living in care, or household adversity such as domestic violence or substance misuse. These experiences often occur alongside poverty and can affect employment and adult living conditions as well as likelihood of harmful behaviours such as drug use, which can ultimately impact on physical and mental health.3,7

What can we do to solve psychosocial pathways to health inequalities?

Tackling psychosocial inequalities takes more than good intentions. To make a real difference, we have to tackle the root causes that trigger these pathways as well as the day-to-day challenges that people are currently facing.

Tackling the root causes

1. Health in All Policies

All policies at local and national government levels should be considered in terms of how they can positively influence psychosocial pathways using instruments like the Mental Wellbeing Impact Assessment tools. These approaches should focus on:1

- Addressing wider social determinants of health that influence how people live and work, including helping to improve employment, housing, education and community networks.

- Tackling conditions that drive poor health in those facing challenges, for example enhancing welfare and other support for people living with mental health issues.

- Empowering communities to have real influence over decisions and use of resources so that people have greater control to make the changes that they need.

2. Early childhood and family support

Early prevention for children and families can have lifelong benefits, for example:1,8,9,10

- Providing greater funding and support to tackle childhood poverty.

- Developing programmes to support good parenting and early detection of adverse childhood experiences.

- Improving quality of early education and support for childhood development.

3. Empowerment for individuals and communities

Collective control and empowerment helps people to buffer the effects of ongoing challenges, and enables communities to design places in which everyone can thrive to tackle root causes of issues. This means:1,11-16

- Supporting communities and professionals to build partnerships as equals, which may require training so that everyone understands their role and can feed into the process.

- Giving communities access to funding and resources, e.g. collaborative commissioning or match-funding.

- Creating spaces for people to connect and share what matters to them, including community hubs.

4. Stigma reduction

Tackling stigma is a key part of equalizing status for different groups. There is limited evidence on the best ways to achieve this, and drivers and solutions will likely differ across groups. A recent review of racial bias in the UK suggested that a multi-level approach is likely to be most effective, including:17

- Living and working conditions: implementing government policies and programmes to address challenges faced by stigmatised communities, relating to both circumstances (e.g. wages) and the stigma itself (e.g. anti-racism education).

- Health services: championing organisational-level initiatives to address racism, diversity training, colocation of health services with social and community services, and leadership buy-in.

- Community networks: involving communities in designing and leading on solutions.

- Individuals: organising group or peer-led education on specific topics, such as screening.

Supporting people to overcome psychosocial challenges

Alongside stopping psychosocial pathways from happening in the first place, we need to support people whose health is being impacted by these pathways already.

1. Social support

We can reduce the impact of stress and psychosocial challenges by helping people to build resilience, self‑efficacy, and control through developing:18-26

- Peer support, befriending, and mentoring programmes.

- Community activities like art, music, and culture.

- Group spaces and activities that encourage belonging, including places of faith and spirituality.

- Social prescribing and programmes to support people with managing challenges.

- Physical activity programmes.

- Volunteering opportunities.

Whilst these are all promising approaches, there is mixed evidence on effectiveness likely because of variation in design across programmes. Further research could help us to identify best practice and how to scale or share this between places.

2. Trauma‑informed care

Understanding the impact of trauma can support services to improve by recognising social context and past trauma so every person feels comfortable, for example by:1

- Focussing on what happened to someone, not just their symptoms.

- Creating safe, trusting environments.

- Building respectful, collaborative relationships between staff and those using services.

- Including peer support and community voice in service design.

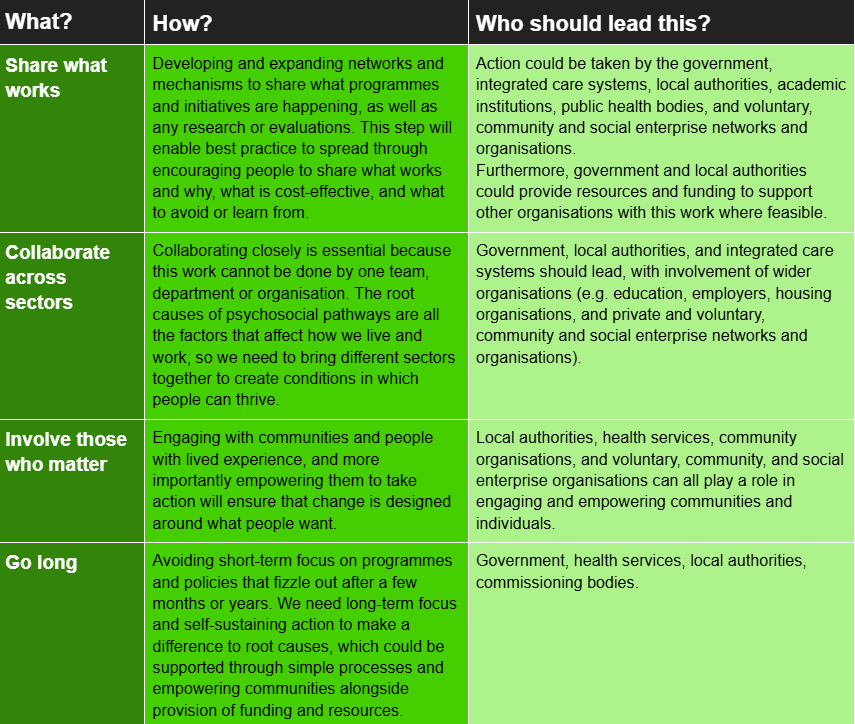

What are the key evidence-based recommendations?

There is no one-size-fits all solution or one organisation who can solve psychosocial inequalities. We have developed some key recommendations that will help to lead to solutions that work at a local, regional and national level to both tackle the root causes of psychosocial pathways as well as to provide help to those who need it right now.

Case studies

A number of organisations, including local authorities, have introduced initiatives which may not have explicitly aimed to tackle the root causes of psychosocial inequalities but may in practice have helped do so. These include:

Building local wealth through co-operatives in Preston27

Based on a cooperative economy model pioneered in the Spanish town of Mondragón, Preston City Council developed the Preston Model, which aims to design policy and action around:

- Shifting public spending to prioritise local businesses, investment in local communities, and support of economic activities to keep wealth within the region.

- Encouraging the growth of worker-owned cooperatives, to build empowerment and capacity within the community.

- Involving “anchor” institutions, such as universities to create a platform for sharing knowledge, lower costs and increase impact.

Since 2013, there have been rises in local procurement, the number of workers earning a Real Living Wage, and the wellbeing and mental health of local residents. Success has been amplified by involvement of the anchor institutions, who support evaluation and enable clear and rapid sharing of learnings both within Preston and to allow wider adoption of the Preston model.

Working across sectors to build good health together across the UK28

The Arts and Humanities Research Council funded multiple partnerships that brought together academics, NHS and public health teams, local authorities, community groups, and people with lived experience. These collaborations were tasked with design and implementation of community engagement projects around the UK, along with collation of case studies to understand themes around the purpose, methods, participants, impacts, barriers and enablers.

This cross-sector collaboration was associated with a range of positive impacts, including benefits for public and community involvement capacity, development of strategies for tackling health disparities, and early evidence of reduced health disparities, such as raised awareness and attendance at breast cancer screenings in one project.

Shaping the future of Bradford with local residents29

Bradford has one of the UK’s youngest and most diverse populations. The Bradford for Everyone programme, which launched in 2019, therefore focuses on engaging community groups throughout Bradford. One of the key projects was the creation of a network of ambassadors. The ambassadors support co-design and evaluation of projects funded through the programme, as well as inputting on local council strategies.

This has led to a wealth of projects that celebrate diversity and tackle key issues for residents, including inequality. For example, the community champions scheme involved over 250 volunteers helping to challenge vaccine hesitancy during the covid pandemic. Across all projects, the clear theme has been creating sustainable projects that lead to long-term change through empowering residents to drive and maintain change.

Emma Butcher, October 2025

References

- Public Health England. Psychosocial pathways and health outcomes: Informing action on health inequalities. 2017. Gov.UK, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a74d3e440f0b65f613228d7/Psychosocial_pathways_and_health_equity.pdf.

- Adler NE, Tan JJX. Commentary: Tackling the health gap: the role of psychosocial processes. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyx167 (last accessed: 10 August 2025)

- Nurius PS, Uehara E, Zatzick DF. Intersection of Stress, Social Disadvantage, and Life Course Processes: Reframing Trauma and Mental Health. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1080/15487768.2013.789688 (last accessed: 10 August 2025)

- Tang KL, Rashid R, Godley J, et al. Association between subjective social status and cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular risk factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010137 (last accessed: 10 August 2025)

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, Link BG. Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. American Journal of Public Health. 2013. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.301069 (last accessed: 10 August 2025)

- Evans GW. Childhood poverty and adult psychological well-being. PNAS. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1604756114 (last accessed: 10 August 2025)

- Morris G, Berk M. Maes M. et al. Socioeconomic Deprivation, Adverse Childhood Experiences and Medical Disorders in Adulthood: Mechanisms and Associations. Molecular Biology. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-019-1498-1 (last accessed: 10 August 2025)

- UCL Institute of Health Equity. The impact of adverse experiences in the home on the health of children and young people, and inequalities in prevalence and effects. Institute of Health Equity website https://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/the-impact-of-adverse-experiences-in-the-home-on-children-and-young-people/impact-of-adverse-experiences-in-the-home.pdf (last accessed: 10 August 2025)

- Faculty of Public Health. Parenting programmes. FPH website. https://www.fph.org.uk/policy-advocacy/special-interest-groups/public-mental-health-sig/better-mental-health-for-all/a-good-start-in-life/parenting-programmes/#:~:text=Examples%20of%20these%20programmes%20include,and%20Family%20Links%20Nurturing%20Programme (last accessed: 14 August 2025)

- The Kids Network. Early intervention for life-changing impact. The Kids Network website. https://www.thekidsnetwork.org.uk/our-impact?gad_source=1&gad_campaignid=22790719866&gbraid=0AAAAADRkgo_cGgLx7acktHR7W4uCybTQI&gclid=CjwKCAjwkvbEBhApEiwAKUz6-7ImZwK0_9WKmlYOuqOlG7oJtbRsKRZ9tA1SB5L73o9o4l1xgxqFmBoCROAQAvD_BwE (last accessed: 14 August 2025)

- NICVA. Community Empowerment Programme (CEP). NICVA website. https://www.nicva.org/cep#:~:text=The%20CEP%20will%20support%20people,and%20deliver%20collaborative%20local%20projects (last accessed: 14 August 2025)

- Fenne D, Chikwira L, Chauhan K. Transforming power relationships in partnership working. The King’s Fund website. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/insight-and-analysis/long-reads/transforming-power-relationships-partnership-working (last accessed: August Aug 2025)

- Community Southwark. The value of collaborative commissioning. SEL strategic alliance website. https://www.selalliance.org.uk/content/the-value-of-collaborative-commissioning?b8010050_page=3 (last accessed: 14 August 2024)

- Costa L, Nieto S. Research Results Community Hubs. SDG lab website. https://www.sdglab.uk/case-study/research-results-community-hubs (last accessed: 14 August 2025)

- Health Creation Alliance. Digging deeper, going further: creating health in communities. The Health Creation Alliance website. https://thehealthcreationalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/THCA-report-_-Digging-deeper-going-further_-creating-health-in-communities-Final-Feb-2021.pdf (last accessed: 10 August 2025)

- East Sussex county council. Appendix A – Review of Community Match. East Sussex county council website. https://democracy.eastsussex.gov.uk/documents/s22555/LMTE%2019%20November%202018%20-%20Community%20Match%20Funding%20-%20Appendix%20A.pdf (last accessed: 14 August 2025)

- Yip JL, Poduval S, de Souza-Thomas L, et al. Anti-racist interventions to reduce ethnic disparities in healthcare in the UK: an umbrella review and findings from healthcare, education and criminal justice. BMJ Open. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2023-075711 (last accessed: 25 August 2025)

- Blodgett JM, Tiley K, Harkness F, et al. What works to reduce loneliness: a rapid systematic review of 101 interventions. J Public Health Pol. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41271-025-00561-1 (last accessed: 10 August 2025)

- Napierala H, Krüger K, Kuschick D, et al. Social Prescribing: Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Psychosocial Community Referral Interventions in Primary Care. Int J Integr Care. 2022. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.6472 (last accessed: 10 August 2025)

- Neumann RJ, Ahrens KF, Kollmann B, et al. The impact of physical fitness on resilience to modern life stress and the mediating role of general self-efficacy. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2022. https://doi.org10.1007/s00406-021-01338-9 (last accessed: 25 August 2025)

- Lancaster MR, Callaghan P. The effect of exercise on resilience, its mediators and moderators, in a general population during the UK COVID-19 pandemic in 2020: a cross-sectional online study. BMC Public Health. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13070-7 (last accessed: 25 August 2025)

- Qiu W, Huang C, Xiao H, et al. The correlation between physical activity and psychological resilience in young students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2025. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1557347 (last accessed: 25 August 2025)

- Nichol B, Wilson R, Rodrigues A, et al. Exploring the Effects of Volunteering on the Social, Mental, and Physical Health and Well-being of Volunteers: An Umbrella Review. Voluntas. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-023-00573-z (last accessed: 27 August 2025)

- Turk A, Tierney S, Wong G, et al. Self-growth, wellbeing and volunteering - Implications for social prescribing: A qualitative study. SSM - Qualitative Research in Health. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmqr.2022.100061 (last accessed: 27 August 2025)

- Howard AH, Roberts M, Mitchell T, et al. The Relationship Between Spirituality and Resilience and Well-being: a Study of 529 Care Leavers from 11 Nations. Advers Resil Sci. 2023. https://doi.org10.1007/s42844-023-00088-y (last accessed: 27 August 2025)

- Ozcan O, Hoelterhoff M, Wylie E. Faith and spirituality as psychological coping mechanism among female aid workers: a qualitative study. Int J Humanitarian Action. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41018-021-00100-z (last accessed: 27 August 2025)

- University of Central Lancashire. Circular thinking: How the Preston Model is creating a sustainable local economy. https://onlinestudy.uclan.ac.uk/resources/how-the-preston-model-is-creating-a-sustainable-local-economy (last accessed 11 September 2025)

- Mughal R, Reynolds R, Thomson LJ et al. Mobilising Community Assets to Tackle Health Inequalities: A synthesis and review of Phase 2 case studies. London: University College London. 2024. Available at: https://ncch.org.uk/uploads/MCA_Phase2_Case_Study_Synthesis.pdf (last accessed: 11 September 2025)

- Niazi Z. Empowering communities to make changes. https://www.local.gov.uk/case-studies/empowering-communities-make-changes (last accessed: 15 September 2025)